Canada and the European Union Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement In late 2016, a new type of court was adopted to resolve investor-state disputes: the Investment Court System (ICS), the same court system previously adopted by the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

But CETA is up and running while TTIP, the proposed agreement between the US and EU, is stalled and not yet implemented. The key takeaway for now, though, is that the ICS is likely to soon become the universal model for all trade treaties.

It is therefore important to examine the nature and background of the ICS. Is it a genuine reform that will solve a problem that benefits everyone, or is it simply a hoax on the public, perpetrated by financial piranhas in cahoots with their government cronies?

“CETA's investor-state dispute settlement rules contain a number of innovations that differ from existing investment treaties. The new courts and rules will serve as a model for future international agreements and will affect Canadian companies investing in the EU,” Canadian lawyers Roy Millen and Mark Claver explained on legal website Break Business Class on December 15, 2016.

As the lawyers further explained: Breaking News: Disputes about Disputes: The Storm Gathers Over ISDS The European Commission announced the adoption of the ICS in 2015, and a press release on September 20 confirmed that ICS is the trend of the future, stating that “the Investment Court system will replace the existing investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism in all current and future EU investment negotiations, including the EU-US TTIP negotiations.”

The same EC press release praised the ICS's perceived benefits, adding: “The proposal for an investment court system is based on significant input received from the European Parliament, Member States, national parliaments and stakeholders through the public consultation on ISDS. The aim is to ensure that all parties have full confidence in the system. It is built on the same key elements as national and international courts, providing for governments' regulatory powers and guaranteeing transparency and accountability.”

That last part is important: as I have found in my research into a range of recent trade issues, the fact that ISDS, the prominent pre-ICS tribunal for resolving disputes, could obtain rulings allowing investors to ignore domestic laws, such as banning or restricting the import of genetically modified foods or requiring certain warning labels on imported tobacco products, to name just two examples, raised strong concerns among observers and politicians, notably Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). National sovereignty itself seemed up for negotiation.

“Investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms in investment treaties allow investors from a signatory country to bring claims of discrimination, nationalization or unfair treatment against the governments of other treaty parties in neutral arbitration,” the two Blake lawyers explained in a more or less neutral opinion. “More than 3,000 treaties covering 180 countries contain such provisions.”

As the lawyers note, countries often agree to investor-state dispute resolution “to reap the benefits of foreign investment,” but critics argue such settlements rely on biased panelists who prioritize corporate interests.

And critics say settlements could hinder governments' ability to regulate in the public interest, undermine transparency, and therefore undermine the democratic process itself. Democracy, in this case, is defined as the ability of a state to make laws and regulations on behalf of its people that govern what can be imported and under what conditions. In a word: consent.

Is ICS just a “rebranding”?

The 36-page report by five progressive groups,The Challenges of the Investment Court SystemFive Key Case Studies of Companies in Trade Disputes, published in 2016, featured five case studies of companies in trade disputes with states.

The report notes: “We wanted to examine whether these cases would no longer be possible under the Investment Court System (ICS) and understand whether that would represent a major shift from the current unfairness of ISDS arbitrations, or whether, as many legal experts and civil society advocates argue, the Commission was simply undertaking a rebranding effort.”

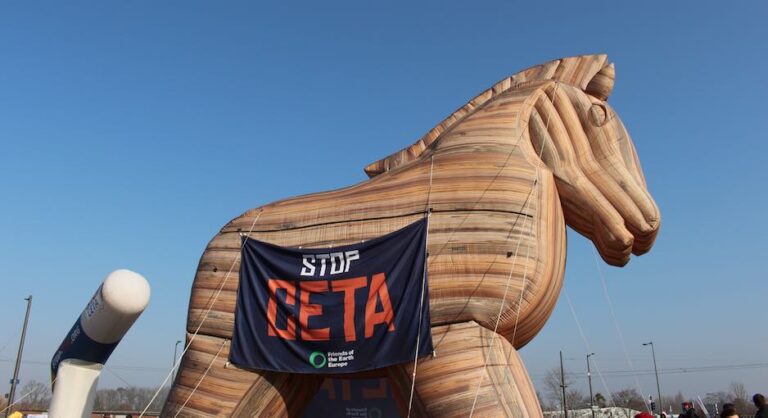

The report was produced by Friends of the Earth, the Transnational Institute, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the Corporate Europe Observatory and the German Environmental and Development NGO Forum.

The report noted that the European Commission's announcement of plans to include far-reaching investor rights in TTIP set the stage for investor attacks on fundamental consumer, labor and environmental protections, “which sparked significant public outcry,” adding that “the Commission was forced to suspend negotiations on this chapter and organize a public consultation, with an unprecedented 150,000 participants, 97 percent of whom unequivocally rejected the inclusion of this mechanism in TTIP in any form.”

The five areas covered in the report are:

- Philip Morris v. UruguayUruguay has mandated tobacco control measures, such as graphic warnings on cigarette packaging, to promote public health.

- TransCanada v. United States About President Barack Obama's decision to reject the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, which would have transported thick tar sands oil from Canada across the central United States for processing at refineries in Texas.

- Lone Pine vs Canada Quebec enacts precautionary fracking moratorium

- Vattenfall v Germany Regarding the imposition of environmental standards by the city of Hamburg on water use at coal-fired power plants

- Bilcon v. Canada Canada has mandated environmental impact assessments and prevented the construction of large quarries and marine terminals in ecologically sensitive coastal areas.

In September 2015, EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström acknowledged that “ISDS is currently the most harmful acronym in Europe,” while Alfred de Zayas, the UN's Independent Expert on Promoting a Democratic and Fair International Order, went so far as to tell the UN General Assembly that ISDS “must be abolished.”

As a result, sensing strong winds of skepticism and opposition, the European Commission announced its intention to “reform” ISDS. By autumn 2015, the Commission presented a proposal for an “Investment Court System” (ICS) to reassure the public that recognizing investor rights would not impede the formulation of public policy. Key elements of this ICS proposal are already included in the EU-Vietnam and EU-Canada CETA agreements.

Regarding the five case studies mentioned above, the report adds: “A detailed analysis of each case shows that any of these contentious disputes could also be brought under the ICS and would likely be successful. Nothing in the proposed rules would prevent companies from challenging government decisions meant to protect health and the environment, nor would anything prevent arbitrators from deciding in favor of companies and ordering states to pay billions of dollars in taxpayer compensation for legitimate public policy actions.”

One particular observation in the report is very suggestive. On page 5 of the report, it states: “The ICS does not limit abusive claims, but rather, unlike existing treaties, explicitly introduces the concept of investors' 'legitimate expectations', thus creating the potential for an increase in arbitration disputes. In all five cases examined, investors alleged a breach of legitimate expectations. According to the proposal, investors can only claim 'legitimate expectations' as a result of 'specific representations' from the government, but this limitation is poorly defined and could mean any measure, action or verbal instruction that, according to the investor, induced a government official to make or maintain an investment.”

The report disputes the European Commission's arguments, arguing that “under the ICS, the interpretation of the broad rights and ill-defined limitations afforded to companies would still depend on for-profit adjudicators and not on public, independent judges,” adding that “they would be paid on a case-by-case basis and loopholes in the EU's proposed conflict of interest requirements would mean that the same corporate arbitrators would continue to sit on arbitration panels. European judges conclude that the ICS proposal does not meet the minimum standards for the judicial profession set out in the Magna Carta of European Judges and other relevant international instruments on the independence of judges.”

Is a “global” court the real goal?

Interestingly, another organization, the American Institute of International Law, Special Reportexpressed a more upbeat assessment of the ICS, arguing that national regulatory rights would be firmly protected.

It notes that the ICS model (which has been incorporated for research purposes into TTIP) is two-tiered and “consists of a Court of First Instance and a Court of Appeal. This Court is made up of (21) members, appointed by the European Union and the United States rather than the disputing parties (investors and host states), and is subject to stricter rules on independence and impartiality. Moreover, the substantive standards are designed to ensure policy space for states to regulate in the public interest.”

What is clear, however, is that the ICS and its inclusion in TTIP and CETA represent what ASIL calls “a fundamental change in the approach to ISDS and brings the serious prospect of a multilateral investment court back onto the diplomatic agenda.”

In other words, ASIL states that “the proposed investment court system has the potential to become a model for a global investment court, in line with the (European) Commission's stated goal.”

That's true. November 12, 2015 European Commission press releaseTrade Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom “Today marks the end of a lengthy EU internal process to develop a modern approach to investment protection and dispute settlement for TTIP. And BeyondIt is the result of extensive consultation and discussion with Member States, the European Parliament, stakeholders and citizens. Play a global role in the path of reform and create an international court based on public trust.(All emphasis added by me)

Notably, the ASIL report implicitly criticizes domestic control of judicial power, stating, on the one hand, that domestic legislation would protect against excessive corporate interference, but on the other hand, it points out that “despite its foresight, the proposed ICS suffers from two structural weaknesses that reduce its suitability as a global model: its bilateral regime and its relationship with domestic courts.”

In other words, while the ICS model clearly points the way towards globalising the trade court, further adjustments are needed to make it a fully-fledged court as originally intended. Thus, in explaining its approach to this issue, ASIL states that the report “details these weaknesses and outlines the changes that can be introduced to transform the investment court system into a vehicle for the true multilateralisation of the ISDS regime.”